What’s New at Home?

In the Land of My Love

An intimate gaze at the domestic sphere, family members, private territory, and the human performance of everyday life, as well as the rooms, furniture items and objects that populate it, are represented in many of the works in the collection. These elements, alongside a concern with the “home” as an idea, ideal, or abstract concept, are the point of departure for the display on this floor, which explores domestic interiors as reflected in Israeli art over the years, from different perspectives and in different contexts.

The concept of “home” in Israeli culture is always suspended between the personal sphere and the collective-national sphere. In both cases, its role is to protect, offer shelter, serve as a place of hiding in times of need, and alsoto define identity and embody the connection to theplace. The construction of a home always involves a process of finding one’s place, which is both internal and external. More than any other concept, “home” in Israeli culture is charged with meanings that exceed its physical existence, transforming it into a symbol – of existence, family, homeland, belonging and security, while also revealing that it might become a destabilized, aggressive and threatening sphere.

The home appears at times as an archetypal image, as is the case in the early works of Moshe Mokady, which describe the country with the enchanting childlike innocence typical of the pre-state period. By contrast, in Mordecai Ardon’s symbolic oeuvre, houses dissolve and disintegrate to represent the destruction of European Jewry’s home. Many years later, the home resurfaced as a marked, flattened, flickering image in the oeuvre of Michal Rovner, or in the iron and earth works created by Micha Ullman. In these cases, it embodies an enduring tension between stability and fragility, permanence and instability, safety and transience.

Other artists represent family members, portraying them either in a tranquil, appeased manner, or through the prism of complex, tense dynamic relations. So, for instance, Michal Gross’ deceased family members – his authoritative father and beloved sister – are transformed in his works into rigid totems imprinted on the home’s beams, walls and doorposts. In a unique self-portrait that is outstanding for its time, he portrays himself as the young, somewhat lost father of an infant lying in a carriage.

The interior spaces of the home, walls, dishes and furniture pieces are represented in numerous works to depict a private, self-enclosed intimate sphere, which also attests to the presence or absence of the home’s inhabitants. At times, the rooms serve as a source of inspiration or point of departure for abstract compositions, as in the paintings of Arie Aroch. In other instances, as in Avigdor Arikha’s paintings, various domestic corners and objects offer an accessible model for painting, a means of underscoring the unfolding of everyday life. And in yet other works, such as the perforated doors in an early work by Sigalit Landau, or the structurally distorted crib with axe-like legs in Yehudit Sasportas’ works, the domestic furniture is transformed from protective to threatening, acquiring a violent charge.

A significant number of works dating to different periods describe a gaze through a window – from the sheltering interior out to the open outdoors – circumscribing the observation of the landscape. In the early works of Reuven Rubin and Israel Paldi from the 1920s, this is a gaze at a local landscape perceived as enchanted; Yehezkel Streichman's studio window in Tel Aviv and the landscape seen from it, which reappear again and again in his works, are transformed into an abstract composition; in David Adika’s photographs, the subject is the dusty, sooty cityscape of contemporary Tel Aviv or that of his native Jerusalem, with its stone houses. Whether real or imagined, the home – with its different parts, intimate spaces, structural signs, residents, and the life unfolding within – appears here as a space of inner wandering, far from national myths and the national ethos; protective and pleasant in some instances, yet also disturbing and destabilizing.

Roni Cohen-Binyamini

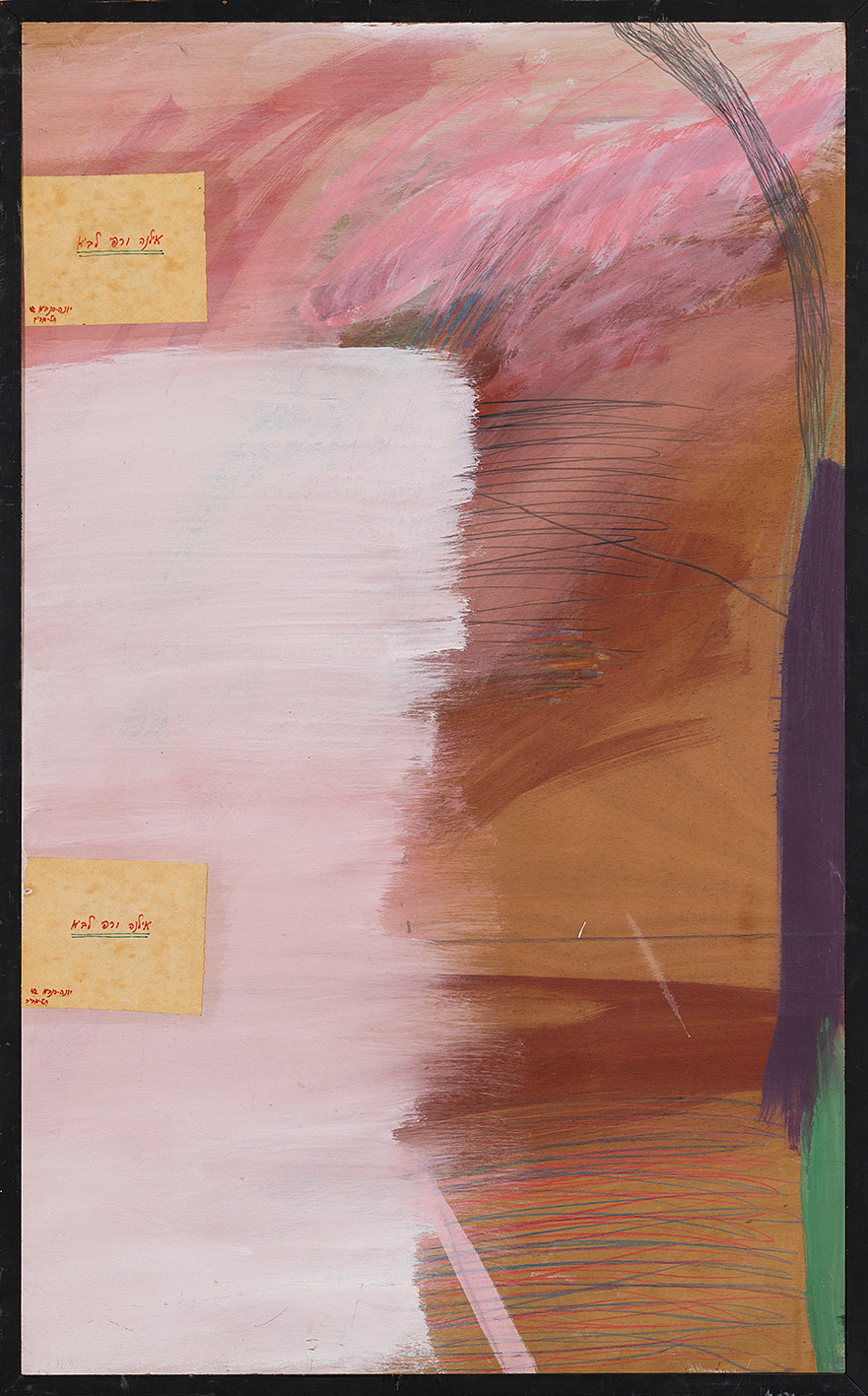

Main image: Lavie Raffi (1937-2007), 1977 ,Untitled

Mixed media on plywood