Body Work

In the Land of My Love

I do not envisage a "history of mentalities" . . . but a "history of bodies" and the manner in which what is most material and most vital in them has been invested.

Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality I: An Introduction, Random House, 1978

The performance of the body and its changing representations in Israeli art are presented in this space as an organizing principal, a proposal for observing the fluctuation of time and place as reflected by, and sedimented, in the body. The body as an emblem of abstract ideas, an object of observation, a metaphor or an arena of action is represented in the works on this floor as a medium inscribed with the cultural spirit and ethos of the time – as well as with power relations, vulnerability, defects, distress and difficulties. The pendulum movement shaping the Israeli story returns in this context, moving between the local sphere and the Diaspora, the material and the spiritual, the terrestrial and the heavenly, the collective and the private.

The redemption of the body played a central role in the Zionist project, as a response to the ills of Jewish life in the Diaspora. Just as the problems of the Diaspora were etched into the image of a sickly, degenerate, limp body, so the New Jew was imagined by means of a healthy body. The diasporic image of the persecuted, helpless Jew inhabiting the realm of the spirit was contrasted with the earthly, strong and sensual figure of the New Jew, who takes his fate into his own hands: the pioneer, laborer or agricultural worker building the country and defending its borders. This allegorical affinity between the building of the body and the building of the nation is given expression, for instance, in Menachem Shemi’s painting Pioneer (ca. 1925). Various responses to this Israeli (and dominantly male) model appeared over time in a range of artworks, both incarnating it and subverting it. So, for instance, one can note the gap between the early works of Reuven Rubin, painted prior to his immigration to the country and characterized by gloomy colors and sickly figures, and between the rich, vital and colorful painterly language of the works created in Israel, which largely represent local figures (including his own figure) as suntanned and physically powerful.

Eastern cultures and the country’s Arab inhabitants were seen from the Romantic, Orientalist perspective of the Zionist settlement project as expressing a natural, ancient and concrete connection with the country. As such, they served as inspiration for the construction of the New Jew, alongside biblical myths and images from ancient Near Eastern cultures and from the Semitic past – as evident, for instance, in Itzhak Danziger’s stone sculptures. The term “Sabra” came to serve as the ultimate representative of this hegemonic model of a native, authentic Israeli – one embodying a direct connection to the place, as well as the values of a society whose simple mannerisms had been liberated from the constraints of European etiquette. This image was enhanced by the legacy of the country’s battles and its culture of bereavement, which gave rise to myths and cultural heroes such as the fearless combatant who is always ready to serve. Incarnations of the Israeli militarist myth are also evident in the carefully staged photographs of Adi Nes from the 1990s, in which images of soldiers are tied to a traditionally Christian iconography and likened to saints and apostles.

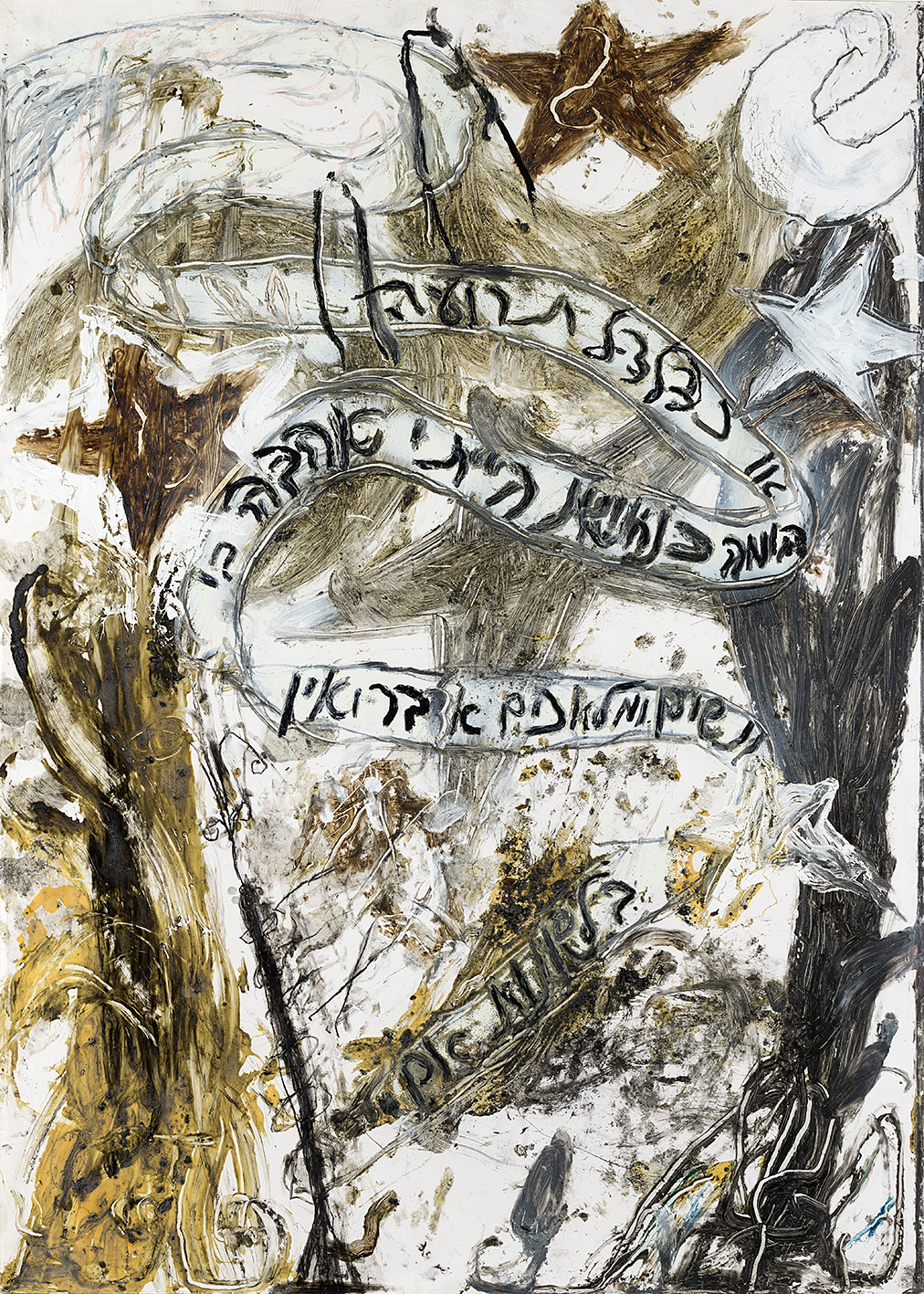

The years following the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War marked the emergence of individualism at the expense of the collective, and were characterized by openness to external cultural influences. These years gave rise to wide-ranging, subversive and rebellious artistic activity, which drew inspiration from the international art arena and was also given expression through the local development of women’s art. The artists who became active in the 1970s, among whom were Yudith Levin and Michal Na’aman, channeled political, moral and gender-related questions into their art-making. The expressive bodies of both male and female artists during those years became an arena for vital, vulnerable, sometimes violent forms of expression, as evident in the works of Igael Tumarkin and Uri Lifshitz. The paintings of Moshe Gershuni, and especially the series of “Soldiers” that he painted in the early 1980s, were characterized by abstract, sensual imagery that alluded to the dissolution of the body, calling to mind bodily fluids and excretions.

The dominance of the Zionist meta-narrative was gradually replaced by alternative (feminist, Mizrahi, Palestinian, homosexual, and religious) narratives, whose treatment of the body began unraveling the existence of a monolithic, homogenous Israeli identity. At the same time, images of the body rooted in the Jewish tradition have continued to surface over the years in Israeli art in the image of golems or shadows. These images allude to the worlds of Jewish magic and mysticism, to diasporic myths of the Wandering Jew, to errant spirits and to the legend of the “Dybbuk,” as well as to the abstract, metaphysical and spiritual presence of prophets and angels.

Roni Cohen-Binyamini

Main image: Moshe Gershuni

Song No. 4 – Through a Galss, Darkly (1 Corinthians 13) From a Series of works based on Brahms Four Serious Songs